Complete Guide to HF Propagation

Complete Guide to HF Propagation, is the reason long-distance radio communication is possible without satellites or repeaters. Signals launched from an antenna can travel thousands of miles by interacting with layers of the upper atmosphere. Understanding how and why this happens gives operators the ability to predict band openings, improve signal strength, and make reliable long-distance contacts.

This guide explains the science behind HF propagation, what affects it, how to predict it, and how to use it to your advantage on the air.

What Is HF Propagation?

HF propagation describes how high frequency radio waves travel through the atmosphere and return to Earth after interacting with the ionosphere. Instead of moving only in straight lines like VHF or UHF signals, HF signals can bend, refract, and reflect due to charged particles high above the planet.

This process allows communication well beyond the visual horizon. A properly launched signal can travel across continents or even circle the globe.

Propagation is not constant. It changes continuously based on solar activity, time of day, atmospheric conditions, and frequency selection. Because of this, HF communication is dynamic and requires understanding environmental conditions.

Please consider Donating to help support this channel

Why HF Signals Can Travel So Far

HF signals travel long distances because of the ionosphere — a region of charged particles beginning roughly 30 miles above Earth and extending hundreds of miles into space.

When solar radiation strikes atmospheric gases, electrons are freed and form ionized layers. These layers can refract radio waves back toward Earth instead of allowing them to pass into space.

When a signal returns to Earth, it can bounce again, repeating the process. Each bounce extends communication range. This is often called skywave propagation.

The Ionosphere and Its Layers

The ionosphere is divided into several layers, each affecting radio signals differently.

D Layer

The lowest layer primarily absorbs radio energy, especially during daylight. It weakens lower HF frequencies and often limits daytime performance on bands like 160m and 80m.

At night, the D layer largely disappears. This is why lower bands improve dramatically after sunset.

E Layer

The E layer can refract some HF signals and occasionally supports medium-distance communication. It is also responsible for sporadic E events, which can produce unusually strong and unexpected propagation.

F Layer (F1 and F2)

The F layer is the most important for long-distance communication. During daylight it often separates into F1 and F2 regions. At night it usually merges into a single layer.

The F2 layer enables global communication because it remains ionized even after sunset and can refract higher frequencies than other layers.

Types of HF Propagation

Different propagation modes determine how signals travel and where they can be heard.

Ground Wave

Signals travel along Earth’s surface. This works best on lower frequencies and over conductive terrain such as seawater.

Skywave

Signals travel upward, interact with the ionosphere, and return to Earth. This is the primary mechanism for long-distance HF communication.

Multi-Hop Propagation

Signals bounce multiple times between Earth and the ionosphere, extending communication range across continents or oceans.

Gray Line Propagation

Gray Line Propagation occurs along the moving boundary between daylight and darkness. Signals can travel efficiently along this transition zone, often producing strong long-distance paths.

Sporadic E

Short-lived but intense ionization in the E layer can reflect higher frequencies than usual, creating unexpected communication paths.

How Frequency Affects Propagation

Each frequency interacts differently with the ionosphere. Choosing the correct band is essential.

Lower HF bands:

- Travel farther at night

- Penetrate the ionosphere less easily

- Are more affected by absorption during daylight

Higher HF bands:

- Work best during daylight

- Require stronger ionization

- Support long-distance paths when solar activity is high

If frequency is too low, absorption increases. If too high, signals pass through the ionosphere into space.

Maximum Usable Frequency (MUF)

The Maximum Usable Frequency is the highest frequency that will refract back to Earth over a specific path.

Above the MUF, signals escape into space.

Below the MUF, communication is possible.

MUF varies constantly based on solar radiation and ionospheric density.

Lowest Usable Frequency (LUF)

The Lowest Usable Frequency is the lowest frequency that can be used for reliable communication.

Below the LUF, signal absorption becomes too strong for effective transmission.

The usable operating window exists between LUF and MUF.

Propagation Topics and Deep Dives

Understanding the fundamentals is only the beginning. HF propagation is influenced by many dynamic atmospheric and solar processes that affect signal behavior in different ways. The topics below explore specific propagation mechanisms and operating strategies in greater depth. Use these guides to expand your knowledge and improve real-world operating results.

Tropospheric Ducting

Learn how temperature inversions and atmospheric layering can trap radio waves and carry them far beyond normal line-of-sight range. This guide explains when ducting forms, how to recognize it, and how operators take advantage of enhanced VHF and UHF signal paths.

Seasonal Propagation Changes

Seasonal propagation shifts throughout the year as solar angle and atmospheric conditions change. This section explains how winter, summer, and transitional seasons affect band performance, absorption levels, and long-distance communication reliability.

Geomagnetic Storms

Solar disturbances like geomagnetic storms can dramatically alter ionospheric stability. Discover how geomagnetic storms disrupt propagation, cause sudden signal fading, or even create unexpected openings. Learn how to read geomagnetic indicators and protect operating plans during solar events.

Band Behavior by Time of Day

HF bands open and close in predictable daily cycles driven by solar radiation. This guide explains which bands perform best during daylight, nighttime, and transitional periods, helping you choose the most effective frequency for any time of operation.

DX Propagation Strategy

Successful long-distance communication requires more than luck. Learn how experienced operators analyze propagation forecasts, select frequencies, time transmissions, and optimize antenna performance to consistently work distant stations.

How Solar Activity Affects Propagation

The Sun drives ionospheric behavior. Increased solar radiation produces stronger ionization, which improves propagation at higher frequencies.

Solar influences include:

- Solar flux level

- Sunspot numbers

- Solar flares

- Coronal mass ejections

- Geomagnetic storms

High solar activity generally improves upper HF band performance but can also create instability.

Geomagnetic disturbances can disrupt the ionosphere and cause sudden signal loss or fading.

Time of Day Effects

Propagation changes dramatically between day and night.

Daytime:

- Higher bands perform better

- Lower bands experience absorption

- D layer present

Nighttime:

- Lower bands improve

- D layer weakens

- Long-distance paths increase

Band selection must follow the Sun’s position relative to the communication path.

Seasonal Propagation Changes

Propagation varies with seasons due to changes in solar angle and atmospheric composition.

Winter often favors lower frequencies with reduced absorption.

Summer can increase absorption but may enhance sporadic E activity.

Seasonal patterns influence band openings and signal strength.

Signal Takeoff Angle and Propagation

The angle at which a signal leaves the antenna determines how far it travels before returning to Earth.

Low angles produce long-distance paths.

High angles produce shorter regional coverage.

Antenna height and design directly influence takeoff angle and therefore communication range.

Propagation Prediction

Because propagation changes continuously, prediction tools and solar data help operators choose the best bands.

Key indicators include:

- Solar flux index

- Geomagnetic activity

- Ionospheric density

- Time of day

- Frequency selection

Experienced operators combine data with real-world listening to determine optimal operating conditions.

Common Propagation Effects

HF signals rarely remain constant. Typical behavior includes:

- Fading — signal strength varies over time

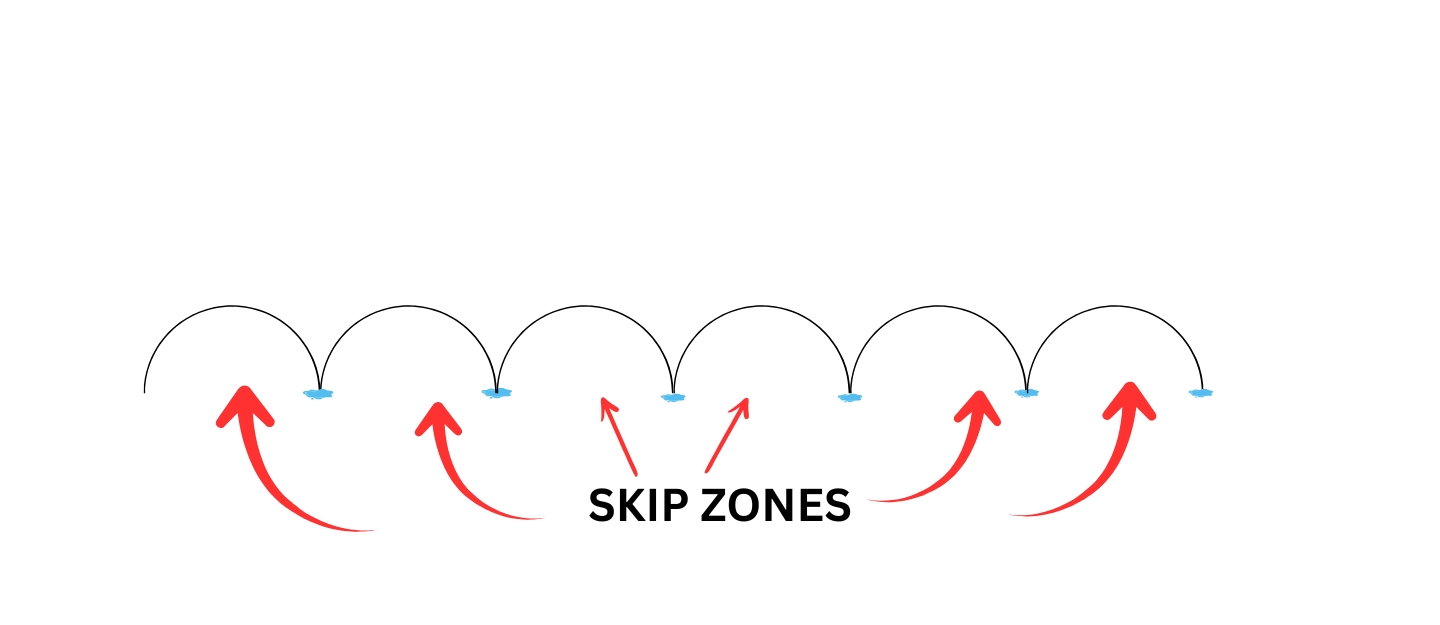

- Skip zones — areas where signals are not heard between hops

- Multipath distortion — signals arriving by multiple paths

- Signal enhancement — sudden strength increases

Understanding these effects improves operating success.

How Operators Use Propagation Knowledge

Successful operators use propagation understanding to:

Select the correct band

Time transmissions for best conditions

Aim signals at target regions

Adjust antenna performance

Predict long-distance openings

Propagation knowledge transforms random operation into strategic communication.

Improving Your HF Propagation Results

To take advantage of propagation:

Use antennas with appropriate height and pattern

Monitor solar and ionospheric conditions

Operate at times favorable for your target region

Experiment with frequency selection

Observe band behavior daily

Experience combined with knowledge produces the best results.

The Role of Propagation in Long-Distance Communication

HF propagation makes global communication possible without infrastructure. By using natural atmospheric behavior, radio signals travel enormous distances using modest power levels.

Every successful long-distance contact depends on understanding how the atmosphere behaves at that moment.

Propagation is not just a theory — it is the operating environment of HF radio.

Complete Guide to HF Propagation

Complete Guide to HF Propagation, this guide explains the fundamentals of how propagation works. The best way to master it is to observe real band conditions and experiment with different frequencies, antennas, and operating times.

Explore the articles below to deepen your understanding and see how propagation behaves in real operating situations.

Please consider Donating to help support this channel