Amateur operators often chase more transmitter power, yet antenna height quietly controls real-world performance. In practice, the take-off angle determines where your signal actually goes. Therefore, understanding this angle explains why a modest station with a well-placed antenna often outperforms a high-power setup with poor geometry. Moreover, physics, not folklore, governs this behavior.

Defining Take-Off Angle

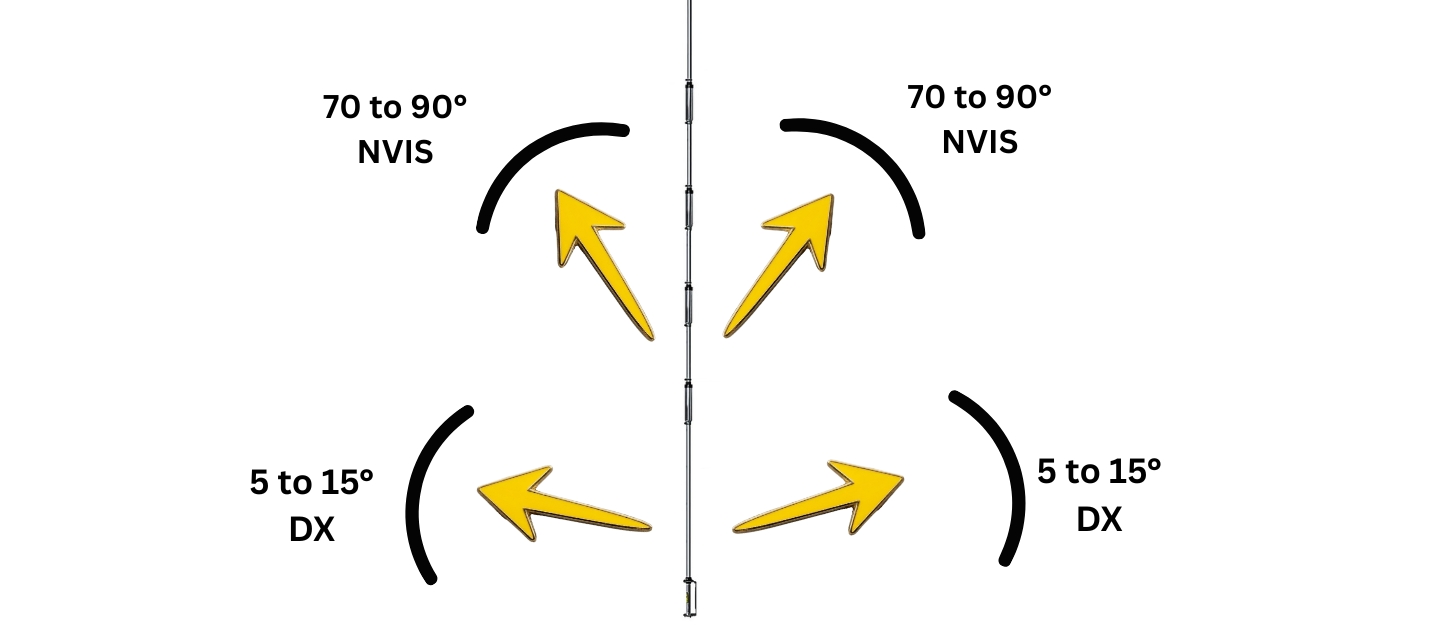

The take-off angle describes the vertical angle at which the strongest portion of your radiated signal leaves the antenna. In simple terms, it shows whether energy launches low toward the horizon or high into the sky. This angle dictates skip distance, coverage footprint, and reliability. Although operators often discuss antennas in terms of gain, the take-off angle frequently matters more.

How Electromagnetic Waves Leave an Antenna

An antenna does not shoot energy in a straight line. Instead, it launches electromagnetic waves that interact with the ground, nearby objects, and the atmosphere. As a result, the radiation pattern forms lobes at specific angles. Therefore, antenna height above ground reshapes these lobes and shifts where maximum energy travels.

Ground Interaction and Wave Reflection

When radio waves strike the ground, they reflect and combine with the direct wave from the antenna. This interaction creates constructive and destructive interference. Consequently, certain angles strengthen while others weaken. As antenna height increases, the reflected wave arrives with a different phase relationship. Therefore, the strongest lobe often moves lower toward the horizon.

Why Lower Take-Off Angles Travel Farther

Lower take-off angles place more energy nearly parallel to Earth’s surface. Because of this geometry, the signal reaches the ionosphere farther away. Then, the ionosphere can refract the signal back to Earth at distant locations. In contrast, high-angle radiation returns to Earth quickly, producing short skip or regional coverage. Thus, height directly controls distance.

Antenna Height Measured in Wavelengths

Physics measures antenna height most accurately in wavelengths, not feet or meters. For example, a 20-foot antenna behaves very differently on 40 meters than on 10 meters. Therefore, as frequency changes, the same physical height produces a new take-off angle. Consequently, multiband performance varies dramatically even with the same antenna.

Power Versus Geometry

Power increases signal strength equally in all directions allowed by the radiation pattern. However, power cannot change the pattern itself. Therefore, if most energy launches upward, more watts simply make the sky brighter. In contrast, raising the antenna reshapes the pattern so more energy leaves at useful angles. Thus, geometry beats brute force.

The Myth of “More Power Fixes Everything”

Many operators assume additional power compensates for poor placement. Although power can overcome some losses, it cannot fix an inefficient launch angle. Consequently, stations with high power but high take-off angles often struggle with DX. Meanwhile, lower-powered stations with optimal height consistently achieve longer contacts.

Near Vertical Incidence Skywave and High Angles

High take-off angles serve a purpose in specific cases. For example, near vertical incidence skywave relies on steep radiation to cover nearby regions. Therefore, low antennas intentionally produce high angles for regional nets and emergency work. However, this same configuration limits long-distance communication.

Height, Current Distribution, and Radiation Lobes

As antenna height increases, current distribution along the radiator interacts differently with ground reflections. Consequently, additional lobes may form, and the primary lobe often lowers. Therefore, even small height changes can produce noticeable differences on the air. This sensitivity explains why moving an antenna a few feet can transform performance.

Real-World Height Constraints

Operators rarely enjoy unlimited tower height. However, even modest increases matter. For instance, raising an antenna from one-quarter wavelength to one-half wavelength can dramatically lower the take-off angle. Therefore, careful planning yields large gains without exceeding practical limits.

Horizontal Versus Vertical Antennas

Horizontal antennas depend heavily on height for angle control. As height increases, their low-angle performance improves significantly. Vertical antennas already favor low angles, yet ground quality and radial systems still influence results. Consequently, height and ground system design work together to define the final pattern.

Terrain and Local Environment Effects

Real ground deviates from textbook assumptions. Sloped terrain, water, and soil conductivity all alter reflections. Therefore, antennas near saltwater often achieve exceptionally low take-off angles. Similarly, antennas on hillsides may favor certain directions. Thus, location amplifies or diminishes the benefits of height.

Practical Implications for Station Design

When designing a station, prioritize antenna height early. Then, choose power levels that support, rather than compensate for, geometry. Moreover, evaluate performance by listening reports and propagation results, not just theoretical gain. Consequently, informed adjustments lead to predictable improvements.

Ideal Take Off Angle

For DX communications, operators usually chase a low takeoff angle because it launches RF energy toward the horizon instead of straight up. In general, angles between about 5 and 15 degrees work best for long-distance paths, especially on the HF bands.

At these shallow angles, the signal reaches the ionosphere farther away, refracts efficiently, and then returns to Earth hundreds or even thousands of miles from the transmitting antenna. As a result, more of your transmitted power contributes to usable skywave propagation rather than being wasted on high-angle radiation that favors short-range contacts.

However, the ideal takeoff angle never exists in isolation. Antenna height, ground conductivity, operating frequency, and ionospheric conditions all shape the final radiation pattern. For example, raising a horizontal antenna generally lowers its takeoff angle, which improves DX performance.

A higher frequencies naturally support lower angles during good propagation. Therefore, successful DX operators focus less on a single “magic” number and more on creating an antenna system that consistently favors low-angle radiation under real-world conditions.

Measuring and Observing Take-Off Angle

Operators cannot easily measure take-off angle directly. However, on-air results provide clear clues. For example, strong distant reports paired with weak local signals indicate a low-angle pattern. Conversely, strong local coverage with limited DX suggests high-angle dominance. Therefore, careful observation reveals the physics in action.

Take-Off Angle: Height as the Silent Amplifier

Antenna height acts as a silent amplifier that reshapes energy instead of merely boosting it. Because physics governs wave interaction with the ground, height determines where signals travel. Therefore, understanding take-off angle empowers operators to make smarter decisions. In the end, raising the antenna often delivers more real-world performance than adding another hundred watts.

Please consider Donating to help support this channel