In radio, audio, and electrical engineering, understanding impedance will show how a circuit resists and responds to alternating current. While resistance opposes current flow in direct current systems, impedance expands the concept to alternating current by including both resistance and reactance.

Therefor, impedance determines how efficiently energy moves between components, antennas, and transmission lines. Understanding impedance is essential for anyone working with electronics, since it directly affects performance, efficiency, and signal quality.

Breaking Down the Components

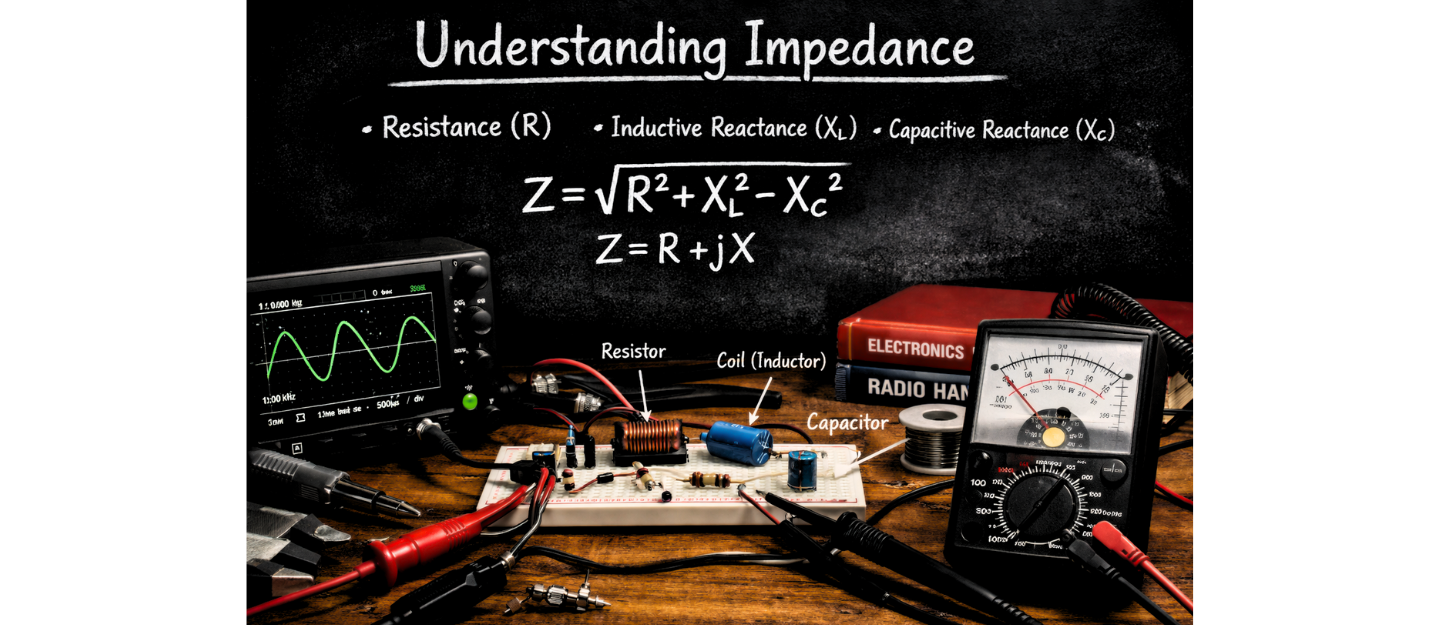

Impedance is a complex quantity that includes resistance and reactance. Resistance represents the part that turns energy into heat. Reactance, on the other hand, represents how capacitors and inductors store and release energy in a circuit. Together, they form a vector relationship, meaning it has both magnitude and phase.

Mathematically, it uses the symbol Z and is measured in ohms. Resistance appears as the real part of impedance, while reactance appears as the imaginary part. Because alternating current constantly changes direction, the balance of inductive and capacitive reactance determines how current leads or lags voltage. Consequently, impedance is not just about magnitude but also about timing between current and voltage.

How Impedance Works in Circuits

When alternating current passes through a resistor, voltage and current remain in phase. However, when it passes through a capacitor, current leads voltage. Conversely, when it passes through an inductor, voltage leads current. The combination of these effects defines total impedance. For this reason, different circuit designs can either cancel or reinforce reactance. By adjusting the balance of capacitance and inductance, engineers create circuits that resonate at specific frequencies.

Transmission Lines

Impedance plays a crucial role in radio systems, especially with transmission lines and antennas. Every coaxial cable or waveguide has a characteristic impedance, usually 50 or 75 ohms. This value represents the balance between capacitance and inductance per unit length of the cable.

When an antenna matches the impedance of the transmission line, energy flows efficiently. However, if it differs, reflections occur. These reflections create standing waves, reduce power transfer, and sometimes damage transmitters. Therefore, impedance matching ensures maximum efficiency.

Matching and Standing Wave Ratio

Operators often measure the Standing Wave Ratio, or SWR, to evaluate how well an antenna matches the transmission line. A perfect match produces an SWR of 1:1. If impedance differs, the SWR rises, and more energy reflects back toward the transmitter. Furthermore, mismatched impedance causes distorted signals and wasted power.

To solve this, operators use tuners, matching networks, or antenna adjustments. Each method works by altering the circuit so that impedances align, allowing smooth energy transfer.

Impedance in Audio Systems

Impedance also affects microphones, speakers, and amplifiers. A low-impedance microphone typically matches professional equipment, while high-impedance microphones work better with consumer devices.

In audio, mismatched impedance can reduce volume, cause distortion, or change tonal quality. Additionally, amplifiers must match the impedance of connected speakers to avoid overheating or failure. Because of this, understanding impedance helps audio engineers maintain both clarity and reliability.

Understanding Impedance in Power Systems

In large power systems, impedance limits current flow during faults. Engineers calculate system impedance to design protective devices that prevent damage. Moreover, impedance affects voltage regulation in transformers and transmission lines. A high impedance in the wrong place leads to voltage drops and reduced efficiency. Consequently, managing impedance is central to stable and safe power distribution.

The Role of Reactance in Impedance

Reactance changes with frequency, which makes impedance frequency-dependent. A capacitor’s reactance decreases as frequency rises, while an inductor’s reactance increases with frequency.

This behavior explains why filters work. By combining inductors and capacitors, engineers design circuits that pass certain frequencies while blocking others. Furthermore, antennas rely on resonance, where inductive and capacitive reactance cancel out, leaving only resistance. At this point, impedance becomes purely resistive, allowing maximum power transfer.

Impedance and Resonance

Resonance occurs when the reactance of a capacitor equals but opposes the reactance of an inductor. As a result, their effects cancel, and impedance drops to a minimum. This property is fundamental in radio tuning, where circuits resonate at a chosen frequency.

At resonance, the antenna or circuit absorbs maximum energy, and signals become strongest. Moreover, resonance makes filters sharp and selective, which is essential for separating signals on crowded bands.

Practical Examples

Consider a simple dipole antenna. At its resonant frequency, the impedance is close to 50 ohms, which matches most coaxial cables. As a result, energy flows efficiently from the transmitter to the antenna. However, if you operate the same antenna outside of resonance, impedance rises, causing reflections.

Another example lies in audio: connecting an 8-ohm speaker to an amplifier rated for 4 ohms creates stress and distortion. These examples show how impedance affects real-world performance.

Advantages of Understanding Impedance

When operators understand impedance, they gain control over efficiency and reliability. They can design circuits that waste less energy, improve signal clarity, and reduce interference. Furthermore, they can troubleshoot mismatches and avoid equipment damage. Knowledge of impedance also allows experimentation with antennas, filters, and amplifiers to optimize performance.

ethernetChallenges and Misconceptions

Many beginners confuse impedance with simple resistance. While related, they differ in how they handle alternating current. Another common misunderstanding is assuming impedance remains constant across frequencies.

In reality, impedance changes with conditions, components, and environment. Therefore, measuring and adjusting impedance requires both theory and practical tools such as analyzers and bridges.

Understanding Impedance Conclusion

Impedance is more than resistance; it represents the complete opposition to alternating current, including both magnitude and phase. Impedance determines how energy flows through circuits, how antennas radiate, and how audio systems sound. Furthermore, impedance matching ensures efficient transfer of energy and prevents damage.

Learning how resistance and reactance combine, operators and engineers can master one of the most fundamental concepts in electronics. Ultimately, understanding impedance opens the door to designing, operating, and troubleshooting systems with greater confidence and success.